Many in the agile space hold up empiricism - the belief that we can gain insight into the world by sensing or measuring it - as the best way to go about our work. In fact empiricism is explicitly referenced in the Scrum Guide. If we don’t want to be all touchy feely and more yknow scientific we should study the world more systematically and objectively. So we should be empirical in our approach. In this post we’re going to look at a critique of empiricism, and specifically reductionist empiricism, starting with the 20th Century’s most famous experiment1.

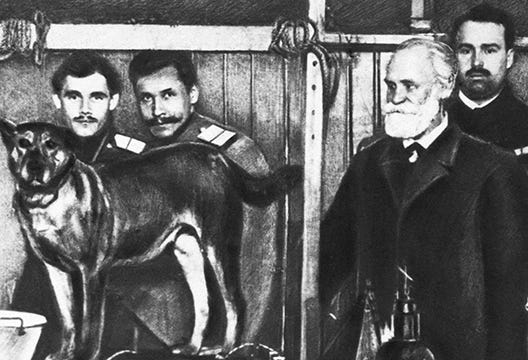

Pavlov and his salivating dogs have woven its way into our collective cultural imagination like few other experiments. However, Pavlov’s experiments may not mean what you think they mean.

Ivan Pavlov was an early behaviourist - which means he was from the early 20th Century tradition of scientists who were interested in understanding cognition and learning by looking at behaviour. Behaviour is concrete, behaviour can be observed.

Like a good empiricist, Pavlov wanted reproducible experiments with repeatable results like a physics experiment. In this approach you work out what you want to measure. You put controls in place to isolate the thing you are looking for. You change one of the variables and see if it has the impact that you expect.

Pavlov noticed that dogs naturally salivate when they are presented with a piece of meat. He termed the presenting of the meat the ‘unconditioned stimulus’ and the salivating as the ‘unconditioned response’. Ie these are what happen naturally without any learning or conditioning.

Pavlov wanted to know if ringing a bell after giving the dog some food would lead to the dog salivating - he wanted to ‘condition’ the dog to respond to the bell even in the absence of food. The bell is the ‘conditioned stimulus’ and the salivating in response would be the ‘conditioned response’.

He set up an experiment where a bell was rung after his lab assistant presented the food. Lo and behold, when the assistant came in after the conditioning and rang a bell, the dog salivated. So the bell (conditioned stimulus) caused the salivating (conditioned response). Right?

Well, it’s not so simple.

Lesser known than Nobel Prize winner Pavlov is the Polish scientist Jerkzy Konorsky who replicated his experiments. He followed Pavlov’s meticulous instructions to the letter with one key exception - when it came time to demonstrate the conditioned response he removed the clapper of the bell, unbeknownst to the assistant who was to be ringing it.

The dog still salivated! It appeared that the dog had probably been conditioned to the appearance of the researcher bearing food, and not the bell itself. In the words of Austrian Cyberneticist Heinz Von Foerster ‘the bell was a stimulus for Pavlov, but not for the dog’.2

The dangers of reductionism

Pavlov’s experiments about conditioning were based on an assumption that the world is reducible. If I want to study behaviour, maybe I can start with the simple reflex, and strip away everything but the reflex to study it. That will give me a building block, and if I have enough building blocks maybe I can understand more complex behaviour and cognition.

This approach has significant problems. The experiments on which Reflex Theory rests were all done in very weird conditions that were set up to make a clean experiment. BF Skinner shoved pigeons in boxes to remove any other stimuli and then studied their behaviour, as if that tells you anything about the normal life or coherent behaviour of a pigeon.

As Philosopher Mazviita Chirimuuta of the University of Edinburgh puts it in The Brain Abstracted:

Although Pavlov performed his conditioning experiments on animals whose nervous systems were unharmed, he still faced the criticism that the artificiality of his experimental setup—such as the confinement and isolation of the dogs—placed limitations on what could be inferred from his results about learning and behavior in general. Goldstein (1934/1939, 175) argues that the precise, repeated paring of unconditioned and conditioned stimuli does not occur in the lives of animals away from human control. Thus, they do not help to explain animals’ learning in the wild, but they do shed light on the processes in play during human training of animals (Goldstein 1934/1939, 178)

Many of the experiments didn’t even yield the kind of stable, repeatable results that you might have expected. Chirimuuta again:

Regarding the conditioned reflex of Pavlov, Merleau-Ponty (1942/1967, 58), following Buytendijk and Plessner (1936), argues that it is too unstable to do the theoretical work required of it. A striking case of instability comes from Pavlov’s reports of the behavior of two dogs that had been subjected to repeated conditioning experiments. They appear to fall into a hypnotic stupor and fail to give the expected reactions to either the conditioned or unconditioned stimuli.

Despite these problems, the reductionist view that we can separate complex behaviour into smaller, simpler chunks has persisted both in science and in popular imagination.

You could argue that what partly happened with Reflex Theory is that the scientists studying it were looking to discover a pattern in the world, driven by an atomistic (and theological, according to Chirimuuta) belief in the simplicity of reality. When confronted with evidence that their theories lacked some of the explanatory power they were looking for, or were not applicable more generally or not even that stable under inspection, they explained them away. The theory is correct of course, but it just needs some ad hoc exceptions to it.

The salivating dogs were explained by the bell, and the appearance of scientists, and probably a bunch of other things not visible to anyone. The behaviour - to the extent that it occurred in any meaningful sense at all - isn’t necessarily behaviour that really matters in the context of a living organism and therefore doesn’t tell us much about the world at all, it just tells us about the experimental conditions.

Agile reductionism

I see the same behaviour sometimes in the community of people who care about how work gets done. Tell me if this is familiar - you go on a training course where together you read the Scrum Guide and learn how Scrum works and you get a shiny certificate. You’ve learnt some theory. Some simple, reduced theory.

You come back to your team with the zeal of the convert and when they don’t yield to your superior logic about how to handle their meetings and workloads you start to think that maybe they are the problem. The people who object to the new ways of working are ‘stuck in the old ways’. The leaders who don’t obviously see why they should bend to your requests are suffering from ‘the wrong mindset’.

Software developers who like to pair programme are forward thinking, and people who don’t like to share their opinions in public are introverts to be coddled. Managers who have been running a particular service for years in a certain style are ‘command and control’ and must be eliminated or transformed.

I hope I’m satirising here but the point is that reality is more complex and nuanced than our labelling permits. Whenever we see a pattern in the world we should view it with a healthy skepticism. Pavlov’s experiments weren’t junk (I’m sure he would have been delighted to hear that I think that), but they only reveal a certain type of insight in a certain limited way. They didn’t build the foundations for an understanding of cognition and all behaviour, but they did allow an unnamed Substack writer to teach my his dog that that the Jewish folk song Hava Nagila means it’s time for walkies.

We should be careful when using reductionist, simplifying theories of what’s working in our teams. If you introduce a tool or a framework to your team and it seems to make everything better you should approach the causality with a healthy skepticism. Maybe any intervention would have made things better and the time was just ripe for change. Maybe things aren’t as better as you’d like to believe. Maybe it made some things better and other worse. Be careful about saying ‘x worked last time for y and z reasons, therefore it will work this time’.

This is a problem that arises when we treat complex adaptive systems with empiricism. Someone has to interpret the empirical results, and that person will come to those interpretations with certain assumptions and biases which may lead them astray. In our complex and entangled world it’s often impossible to draw the lines about where cause and effect lie, especially when we are trying to match theory to reality. I can be as empirical as I like, but I might be measuring the wrong things, or drawing questionable conclusions.

Much better is to be able to - yes - bring past experience to present circumstance, but to do so with a healthy skepticism. To experiment, even with things that for you feel inviolable. Not every team needs scrum, not every team will respond well to Liberating Structures. Some teams need more efficiency, and some need more effectiveness. Some more time alone, some more time together. Tread carefully, infer at your own risk.

maybe.

I haven’t been able to find any evidence that this story actually happened with Konorsky other than this verbal retelling from Von Foerster. a) I don’t think this story needs to be true to be true b) it may have still happened and would love if someone could provide me a link.